Georgia Emerging As Test Case for Russia Relations “Reset”

by James Colbert

by James Colbert

Signs of a Cold War style confrontation between the United States and Russia are in evidence over Moscow’s ongoing attempts to intimidate the democratic and West-embracing government of Georgia. Earlier in 2010, Russia declared that it would establish military bases on land it occupies in the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and this week Moscow announced it would deploy the advanced S-300 anti-aircraft missile system in Abkhazia. The S-300, with a range of 90 miles, covers nearly half of Georgian airspace. It was just six weeks ago, on July 5 that the United States laid down clear markers that the Obama Administration’s “reset” of relations with Russia would not excuse such bellicosity.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, speaking that July day from the presidential palace in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, declared, “The United States does not recognize spheres of influence.” Clinton’s declaration undoubtedly brought relief to Georgians who had felt a bit left off of the Obama Administration’s list of foreign concerns. None less so than Nikoloz Vashakidze, Georgia’s Deputy Defense Minister, who briefed JINSA leaders in Washington late last month on the ongoing effects of Russia’s occupation of those territories that comprise one fifth of Georgia’s territory. His comments echoed those JINSA members heard from government officials in Tbilisi the first week of May during a four-day visit to the country.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, speaking that July day from the presidential palace in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, declared, “The United States does not recognize spheres of influence.” Clinton’s declaration undoubtedly brought relief to Georgians who had felt a bit left off of the Obama Administration’s list of foreign concerns. None less so than Nikoloz Vashakidze, Georgia’s Deputy Defense Minister, who briefed JINSA leaders in Washington late last month on the ongoing effects of Russia’s occupation of those territories that comprise one fifth of Georgia’s territory. His comments echoed those JINSA members heard from government officials in Tbilisi the first week of May during a four-day visit to the country.

Will America’s Strong Words Be Enough?

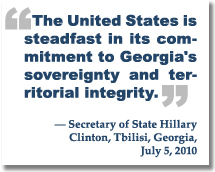

In the boldest such statement yet by the U.S. Government, Clinton condemned Russia’s “invasion and ongoing occupation” of Georgia. In fact, it was quite possibly the first time a senior U.S. official described Russia’s military presence in Abkhazia and South Ossetia as an occupation. Assuring her audience of the White House’s commitment to embattled young democracies, the Secretary of State told her audience that “President Obama and I have also communicated this message directly to our Russian counterparts … [W]e continue to call for Russia to abide by the August 2008 cease fire commitment signed by President Saakashvili and President Medvedev, including ending the occupation and withdrawing Russian troops from [the Georgian territories of] South Ossetia and Abkhazia to their pre-conflict positions.”

The strong statement was made on the last day of the Clinton’s four-day tour through former Soviet-bloc countries. Addressing an international meeting of democratic leaders in Krakow, Poland on July 3, Clinton said, “We must be wary of the steel vise in which many governments around the world are slowly crushing civil society and the human spirit.”

Ever since the 2008 Russian invasion, it has been an uphill battle for Georgia to even get the world to pay attention to its precarious situation. Vashakidze, in Washington for meetings with his counterparts at the Pentagon, discussed what he called Georgia’s “quite serious PR war with Russia.”

The Russian Narrative Dominates Global Media

Speaking in JINSA’s Washington office, Vashakidze said that, unfortunately for Tbilisi, global media outlets nearly exclusively have followed the Russian narrative regarding the causes and conduct of the August 2008 war. More worrisome, he said, Moscow is creating an atmosphere tolerant of further military actions by its armed forces.

Russia is currently nearing completion of a military buildup in South Ossetia and Abkhazia which is clearly offensive in nature and includes the stockpiling in South Ossetia of a greater amount of munitions than the number of troops currently deployed there could use in addition to armored units and bridging equipment, Vashakidze said. The obvious conclusion is that the materiel is pre-positioned to enable a rapid assault on Tbilisi, which lies but 50 road miles from the South Ossetia regional boundary, he said.

Russia is currently nearing completion of a military buildup in South Ossetia and Abkhazia which is clearly offensive in nature and includes the stockpiling in South Ossetia of a greater amount of munitions than the number of troops currently deployed there could use in addition to armored units and bridging equipment, Vashakidze said. The obvious conclusion is that the materiel is pre-positioned to enable a rapid assault on Tbilisi, which lies but 50 road miles from the South Ossetia regional boundary, he said.

Vashakidze noted that Georgia has an urgent need to purchase anti-armor weapons to deter further Russian assaults. The West, including the United States, heretofore Georgia’s greatest benefactor, has imposed a total but not publicly disclosed arms embargo on Georgia. Ostensibly this was to encourage Tbilisi to develop education, training and doctrine in the military sphere before rearming but it appears to many observers more to be an attempt not to anger Moscow.

Prior to Russia’s August 2008 attack on Georgia, Israel had been a leading partner selling Georgia military systems and providing training and combat expertise. Today, however, Vashakidze said, Moscow holds cooperation on the Iranian nuclear issue as leverage over Jerusalem not to sell arms to Georgia. Furthermore, he continued, U.S. government policy since the short August 2008 war has been to discourage any other country from selling weapons to Georgia so as to not “inflame tensions.” Meanwhile, Vashakidze said, Russia is concluding weapons deals with Armenia and Azerbaijan in an attempt to surround Georgia with well-armed client states and is expanding a military base in Armenia.

Placating Russia on Iran Overrides U.S. Anger at Russian Aggression

The desire to keep Russia on the reservation as far as Iran is concerned has led the U.S. government to acquiesce on a range of Moscow’s disturbing behaviors from backing off on inducements to Ukraine to hew to a path between the Kremlin on one side and the EU and NATO on the other to a seeming tolerance for Russia’s occupation of Georgian territory. Defense News reported May 31 that the White House has lifted sanctions on Russian defense companies and universities involved in defense research that had been accused of assisting Iran with its nuclear weapons program and of proliferating ballistic missile technology. According to the article, “That means Russia is free to sell the S-300 advanced anti-aircraft missile system to Tehran.”

“The United States is steadfast in its commitment to Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity,” Clinton, with President Mikheil Saakashvili at her side, declared in Tbilisi. If taken at her word, the Secretary has carved out a large piece of work for herself. Russian troops occupy 20 percent of Georgian territory. The Russian client governments in Abkhazia and South Ossetia are recognized only by Russia, Nicaragua, Venezuela and Nauru.

In Tbilisi, Clinton recognized that Russia has prevented EU cease-fire observers from entering the occupied zone, “We also stressed the need for humanitarian access to the territories. And we will continue to work toward a peaceful resolution of the conflict through established international mechanisms and constructive non-violent channels.” Currently, international observers can only work from the Georgian side of the cease-fire lines. Observer missions from the Organization for Security Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and the UN (the United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia) had been working in Georgia since 1993. The Russian government used its membership in those organizations to have the missions withdrawn. Vashakidze noted that the absence of a large-scale international presence along the cease-fire lines encourages Moscow’s belief that it has a free hand.

In Tbilisi, Clinton recognized that Russia has prevented EU cease-fire observers from entering the occupied zone, “We also stressed the need for humanitarian access to the territories. And we will continue to work toward a peaceful resolution of the conflict through established international mechanisms and constructive non-violent channels.” Currently, international observers can only work from the Georgian side of the cease-fire lines. Observer missions from the Organization for Security Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and the UN (the United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia) had been working in Georgia since 1993. The Russian government used its membership in those organizations to have the missions withdrawn. Vashakidze noted that the absence of a large-scale international presence along the cease-fire lines encourages Moscow’s belief that it has a free hand.

As the Soviet Union began to disintegrate toward the end of the 1980s and Georgia moved toward independence, Moscow stoked tensions between ethnic groups living in Abkhazia including Abkhaz, Armenians and Russians as well as Georgians. Georgians were the largest ethnic group in Abkhazia. Historically, there has been very little ethnic strife there. In both Abkhazia and South Ossetia, there was a long history of intermarriage and communal harmony and high productivity. Indeed, Abkhazia was long considered to be the most prosperous Georgian region.

The war that flared between 1992 and 1993 resulted in the ethnic cleansing of much of the Abkhazia’s Georgian population. Prior to 1992, ethnic Abkhaz made up less than 40 percent of the population with Georgians a majority. Since 1993, with a boost after August 2008, and in partnership with the pro-Russian client government that took over there, Russia has carried out a virtual annexation of the territory, issuing Russian passports for most of their residents, making Russian the lingua franca and instituting the ruble as the official currency.

In a similar fashion, Russia stoked ethnic tensions in South Ossetia. Instigating a break away government and supporting an allied militia, Moscow instigated the outbreak of several wars in the territory, including a full-on civil war from 1991 to 1992. As a result of the conflict and subsequent pressure from the Kremlin’s puppet regime supported by a strong Russian military “peacekeeper” presence, tens of thousands of Georgians fled their homes leaving the self-styled South Ossetian government in control of a patchwork of territories in the region with Georgian forces in control in the others.

The Georgian government protested Moscow’s increasing economic and political presence in the region and against the depredations of the Russian military-backed Ossetian militia. The United States joined a growing outcry over the so-called Russian “peacekeeping force.” In August 2006, Senator Richard Lugar, the longtime leader of the Foreign Relations Committee, joined with EU officials responsible for the region in declaring that Russia was not a neutral peacekeeper. Lugar was later joined by then-Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Sen. Joseph Biden in sponsoring a resolution accusing Russia of attempting to undermine Georgia’s territorial integrity and called for replacing the Russian-manned peacekeeping force operating under Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) mandate.

The Georgian government protested Moscow’s increasing economic and political presence in the region and against the depredations of the Russian military-backed Ossetian militia. The United States joined a growing outcry over the so-called Russian “peacekeeping force.” In August 2006, Senator Richard Lugar, the longtime leader of the Foreign Relations Committee, joined with EU officials responsible for the region in declaring that Russia was not a neutral peacekeeper. Lugar was later joined by then-Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Sen. Joseph Biden in sponsoring a resolution accusing Russia of attempting to undermine Georgia’s territorial integrity and called for replacing the Russian-manned peacekeeping force operating under Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) mandate.

Little mention has been made of the Russian occupation of another piece of Georgian territory that it is not part of what is traditionally understood to be the “disputed” territories acknowledged by the international community. Even as the 2008 cease-fire was going into effect, Russian troops seized the town of Akhalgori in Georgia’s Mtskheta-Mtianeti region and abutting the South Ossetia administrative zone. Moscow has since changed its name to Leningori and insists that it is part of South Ossetia. Of significant strategic military importance, holding Akhalgori puts Russian armored forces closer to Tbilisi and across the Ksani River significantly cutting down the hours it would take a Russian column to reach Tbilisi. Akhlagori is rarely mentioned outside of the Georgian media.

Russia Sets-Back Georgia’s NATO Aspirations

Russia’s attacks in August 2008 could not have happened without tremendous preparation giving lie to Moscow’s claims that it was reacting to a Georgian attack on South Ossetian government forces in the capital of Tskhinvali. Military provocations and unilateral changes to the status of occupied Abkahzia and South Ossetia took place from 1999 to 2006 including the aforementioned issuing of Russian passports as well as the arming of client militia, economic and trade embargoes and energy cutoffs.

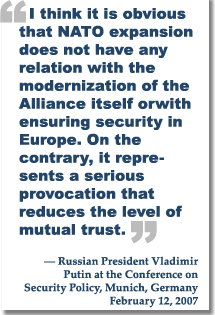

The situation heated up when, on February 12, 2007, then-Russian President Vladimir Putin delivered remarks to the 43rd Munich Conference on Security Policy in which he strongly condemned the contemporary situation with America as the world’s only superpower, criticized American leadership for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and described NATO enlargement as an unchecked threat to Russia. He said, “I think it is obvious that NATO expansion does not have any relation with the modernization of the Alliance itself or with ensuring security in Europe. On the contrary, it represents a serious provocation that reduces the level of mutual trust.”

Over the next year, there were many other incidents of Russian intimidation including attacks in March on the Upper Kodori Gorge, the last place in Abkhazia still held by Georgian forces and the August 7 instance whereby a Russian Su-27 flew into Georgian airspace and launched a KH-58 anti-radar missile that impacted on the ground but failed to explode near the Georgian town of Tsitelubani.

From February through March 2008, Russian leaders, apparently reacting to the successful vote for Kosovo’s independence that they bitterly opposed, issued a series of strong statements to the effect that the pursuit of independence and ties to the West by former Soviet republics and territories threatens Russia.

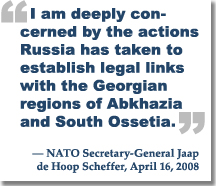

Despite support from the United States and NATO Secretary-General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, NATO members, meeting April 2 to 4, 2008 at the 20th NATO Summit in Bucharest, deferred Georgia’s bid to join NATO’s Membership Action Plan, a necessary step on the path to full membership. It was reported that Germany, heavily dependent on Russian energy supplies, and France led the vote against Georgia, fearful of upsetting Russia.

On April 16, 2008, Russian President Putin signed a decree establishing a range of legal ties between Russia and the puppet regimes in Abkhazia and South Ossetia that marked a dramatic escalation in Moscow’s annexation policy. Moscow’s actions were widely condemned. “I am deeply concerned by the actions Russia has taken to establish legal links with the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia,” Scheffer said.

On April 20, 2008, a Russian MiG-29 shot down an unarmed Georgian UAV over Abkhazia.

Moscow Long Prepared For Its 2008 Invasion

Analysts familiar with the Russian military estimate that it took many months to make the necessary preparations for the invasion especially those concerning the Russian Navy’s transport of 4,000 Russian paratroopers from the Black Sea naval base at Novorossiysk to the port of Ochamchira in Abkhazia and from there down the coast to seize the Georgian port of Poti and the well-coordinated armored thrust through the Roki Tunnel under the Caucasus Mountains into South Ossetia.

All involved Russian military forces were mobilized, trained and exercised prior to the invasion. Additionally, units of so-called volunteers including Cossacks, mostly from the North Caucasus carried out ethnic cleansing of Georgians and non-compliant Ossetians from South Ossetia.

Medical units, fuel depots and munitions were pre-positioned in both Abkhazia and South Ossetia prior to the launching of the August 7 assault. It was reported that beginning on August 2, Moscow brought in compliant journalists to Tskhinvali, the South Ossetian capital. According to Amb. David Smith, Senior Fellow at the Tbilisi-based Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies (GFSIS), writing in the Georgian Daily, July 23, 2010, “Russian forces executed their war plan, including attacks on civilians, complemented by looting, vandalism, rape, murder and, ultimately, ethnic cleansing and occupation” behind a veil of media self-censorship. Meanwhile, Smith wrote, the selected journalists reported, “a tragicomedy of Georgian aggression, even ‘genocide,’ in which Russia alternated between the roles of victim and savior.” A complete timeline of Russian preparations for the attack is meticulously detailed in the book, A Little War that Shook the World: Georgia, Russia, and the Future of the West, by former Assistant Deputy Secretary of State Ronald Asmus, released in January 2010.

A History of Russian Bitterness

The current crisis has immediate roots in Russian anger over Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution that ultimately saw the pro-Western Saakashvili elected president and his party in subsequent control of the Georgian parliament. Recently Russia has been actively backing Saakashvili’s rivals, chiefly Zurab Noghaideli, a former Georgian prime minister, and Nino Burjanadze, former speaker of the Georgian parliament. According to G2 Bulletin, an online subscription-based intelligence newsletter published by WorldNetDaily.com, Putin is using Noghaideli and Burjanadze to convince the Georgian public that Russia could facilitate some form of reunification with Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In fact, the newsletter reported, Putin may well be laying the groundwork to overthrow the Saakashvili government, which the Russian government had declared a “terrorist regime.”

The current crisis has immediate roots in Russian anger over Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution that ultimately saw the pro-Western Saakashvili elected president and his party in subsequent control of the Georgian parliament. Recently Russia has been actively backing Saakashvili’s rivals, chiefly Zurab Noghaideli, a former Georgian prime minister, and Nino Burjanadze, former speaker of the Georgian parliament. According to G2 Bulletin, an online subscription-based intelligence newsletter published by WorldNetDaily.com, Putin is using Noghaideli and Burjanadze to convince the Georgian public that Russia could facilitate some form of reunification with Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In fact, the newsletter reported, Putin may well be laying the groundwork to overthrow the Saakashvili government, which the Russian government had declared a “terrorist regime.”

While Putin’s intent may well be the demise of the Saakashvili government, support for Noghaideli and Burjandze has been miniscule. In the May 30 local elections, Saakashvili’s United National Movement (UNM) secured a overwhelming victory, retaining a majority in all 63 municipal councils outside of Tbilisi and gaining 39 of 50 seats in the Tbilisi City Council, a critical victory as the capital city is home to approximately one-third of Georgia’s population of 3.8 million. The incumbent UNM mayor of Tbilisi, Gigi Ugulava, won the mayoral race with a solid 55 percent of the vote, a significant victory considering Tbilisi is the strongest base for Saakashvili’s opposition.

In her Tbilisi address, Secretary of State Clinton also commented on U.S.-Georgia relations, noting that the United States is “committed to the success of Georgia’s democracy and economy” and is building “on the framework for cooperation that was institutionalized in the U.S.-Georgia charter on strategic partnership last year.” She then noted the U.S. “very much appreciate[s] Georgia’s significant contributions to the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan, and honor[s] its commitment to fighting terrorism around the world.”

Can NATO Save Georgia?

Indeed, seeing NATO as a security guarantee from Russian aggression, Georgia has pursued membership since before the Rose Revolution, and intensified the pursuit during Saakashvili’s presidency, despite the anger it provokes in Moscow. All opposition parties except the Socialist Party support NATO membership and the most recent poll reports 69.9 percent support for Georgian membership in NATO. To bolster its case as a nation willing to support Western security initiatives, Georgia has been working with the U.S. military to bring its forces up to Western standards and has been the largest per capita contributor of combat troops in Afghanistan and the second largest in Iraq.

“As we stand here today,” Clinton said in her Tbilisi speech, “Georgian soldiers are fighting alongside U.S. Marines in Helmand Province, and helping Afghans build a more peaceful future for their own country. And I thank the Georgian people, and particularly the Georgian military, for their service, sacrifice, and bravery. These contributions provide strong evidence of Georgia’s diligent movement toward meeting the requirements for membership in NATO.”

JINSA Delegation Hears First Hand from Georgian Leaders

Deputy Prime Minister and State Minister for Reintegration Temur Yakobashvili speaking to the JINSA delegation on May 7, rhetorically asked, “How many allies like Georgia does the U.S. have around the world? Few … even superpowers need allies.” Already Georgian ports, railroads and airspace are used to transport critical supplies to Afghanistan. He reminded the group that landlocked countries are forced to trade through Russia, which is problematic as Moscow uses this for leverage through such tactics as pipeline “disruptions.” But, he noted that East to West energy routes are also becoming West to East commodity routes and Georgia is well situated to take advantage of that and is working to improve its Black Sea ports and highways for increased truck traffic.

Deputy Prime Minister and State Minister for Reintegration Temur Yakobashvili speaking to the JINSA delegation on May 7, rhetorically asked, “How many allies like Georgia does the U.S. have around the world? Few … even superpowers need allies.” Already Georgian ports, railroads and airspace are used to transport critical supplies to Afghanistan. He reminded the group that landlocked countries are forced to trade through Russia, which is problematic as Moscow uses this for leverage through such tactics as pipeline “disruptions.” But, he noted that East to West energy routes are also becoming West to East commodity routes and Georgia is well situated to take advantage of that and is working to improve its Black Sea ports and highways for increased truck traffic.

Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Giga Bokeria told the JINSA group that the problem with Russia is the Kremlin’s firm belief that Georgia does not deserve to be an independent sovereign state. Following that assertion, he said that Georgia must work to decouple Moscow’s “belief that Georgian successes are Russian setbacks.” Underlying this problem, Bokeria said, is that Russia has not accepted that it needs to refashion itself as a nation state. Under Putin’s leadership, Russia will not give up the concept of empire, he said.

Georgia’s Amazing Post-Soviet Progress, Corruption Nearly Eradicated

Since his first election in 2004 and subsequent reelection in 2008, President Saakashvili has led the implementation of strong anti-corruption laws that have led to a boom in business opportunities in Georgia. In fact, the World Bank’s 2010 “Ease of Doing Business Index” ranks Georgia number 11 out of 183 countries surveyed. This puts Georgia above Japan, Germany, South Korea and Sweden. It is a remarkable achievement for a country that, as previously noted, was considered hopelessly corrupt just 10 years earlier. For comparison’s sake, today Russia is ranked 120 and Ukraine is 142.

Internal Affairs Ministry Spokesman Shota Utiashvili admitted to the JINSA delegation that in the 1990s the police were among the most corrupt institutions in Georgia. Today, however, he said that the police are among most highly trusted Georgian institutions. International Republican Institute polling data show that 81 percent of the citizenry report a favorable opinion of the police, a remarkable turnaround that only came about because of dramatic action taken by President Saakashvili’s government in 2004 when the entirety of the national force was let go. Some four months later a new force, trained with the assistance of police executives from the United States and Western Europe, took over. It was reported that, in the interim, crime rates did not rise owing to the high corruption levels within the old force and the temporary efforts of other national security forces to fill in.

Leading journalist Natia Gogsadze, a reporter for Rustavi-2 TV, the largest private television broadcasting company in Georgia, described the challenge of bringing the country’s media outlets up to Western standards after decades of Soviet-style governmental censorship. She spoke at a roundtable discussion held for the JINSA delegation at the Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies (GFSIS), a think tank located in Tbilisi. In attendance were academics, reporters and analysts from other civil society organizations.

Future Stability Demands Western Resolve

Discussing the weak American and European responses to the Russian invasion of Georgia, Amb. Smith of the GFSIS, noted that the West wants to live in a 21st Century “post-historical world” which it cannot square with the fact that most of the Eurasian countries exist in a 20th Century geopolitical world. Consequently, he said, both Europe and America have missed the geopolitical significance of Russia’s war on Georgia and simply do not understand the ruthless nature of Russia under Vladimir Putin. The sad result, Smith said, is that while Russia invades with tanks, all the West can do is to respond with appeals for peace talks.

– James “Jim” Colbert is a Policy and Communications Director at JINSA and is Deputy Editor of the organization’s Journal of International Security Affairs.